I might be a bad geographer. The possibility has become more apparent since my move to the United Kingdom; potential place pitfalls abound. The first time I took the train to Liverpool, I boarded the “trans-Pennine express,” only belatedly recognizing the implied existence of a landscape feature called the Pennines. Another time I was halfway to Bristol before I discovered that city’s actual location, which, it turns out, is not on the southern coast of England.

At the moment I’m reading a novel in which one of the characters often stops at Bath on the way back to London from Bristol and I’ve realized that either this character prefers really inefficient routing or Bath simply cannot be where I thought it was.

Also, although I can handily locate all 50 US states on a map, I do not know the names or locations of most of their capitals. Bad geographer indeed.

Or maybe I’m a good geographer. After all, when I saw that my Bristol train listed Penzance as its final destination, I was sorely tempted to stay on until the end, just so I could say I’d been there. That is quintessential geographer behavior.

I also have a good geographer instinct for the importance of context, attachment to place, and identity. Which is maybe why that most basic of small-talk questions, “where are you from?” fills me with such ambivalence. On the one hand, I recognize the value of the question for creating inter-personal connection and linking individuals to places. It’s a question I enjoy asking. On the other hand, it’s a question I myself struggle to answer.

I really don’t like to be asked where I’m from.

Where Are You From in Real Life?

One might surmise that my dislike stems from being an American in England—every time I open my mouth, it’s obvious I am not from here. But that’s not it. In fact, the diversity of accents in the UK means that my American twang is merely one of many. In my research group, we have Irish, Singaporean, western isles of Scotland, London, and South and North of England. I hardly stand out.

Or maybe I was scarred from a summer homestay in France in high school, when my host family insisted that the town I said I came from—Nashville, Indiana—was actually quite famous outside the US, especially for music. After a few tries at explaining that the US has limited creativity where place names are concerned (I say that, but a couple of miles outside my Nashville lies the hamlet of Gnaw Bone, Indiana), I gave up and acquiesced to being remembered as the American from Nashville, Tennessee.

It could also be remembering that my 9th grade P.E. teacher rarely called me by name. Instead, when urging me to run faster or kick a ball or pay attention—all of which happened often— he’d yell, “Hey, Indiana!” This was Long Beach, California, in the mid ‘80s and I suppose being from Indiana counted as a distinguishing feature. As the new kid in school that year, I must have responded, “Indiana,” to his off-handed query about my antecedents.

What I definitely remember, with mixed feelings, is that a common question throughout my undergraduate years was, “where are you from in real life?” Pregnant with nuance, the question acknowledged that we were all resident in Bloomington, Indiana, but some of us had come from further away than others. Some of us were less interesting than others. To be from out of state carried the greatest cachet; to be a townie, the least. Almost as bad was to have moved just 16 miles for college. This wasn’t to be admitted, if possible.

Yes, but Where Are You Really From?

I am hyper-aware, as I write this, that my qualms around the question are different than for others, especially people of color, who experience “where are you from?” as a deliberate or unintentional form of exclusion. For many, it’s a loaded question that implies they don’t belong or fit in, often in their own home town or country.

These matters are important, and by talking about my own comparatively benign experiences here I do not mean in any way to discount others’ different and more difficult experiences.

Too Much (Geographical) Information

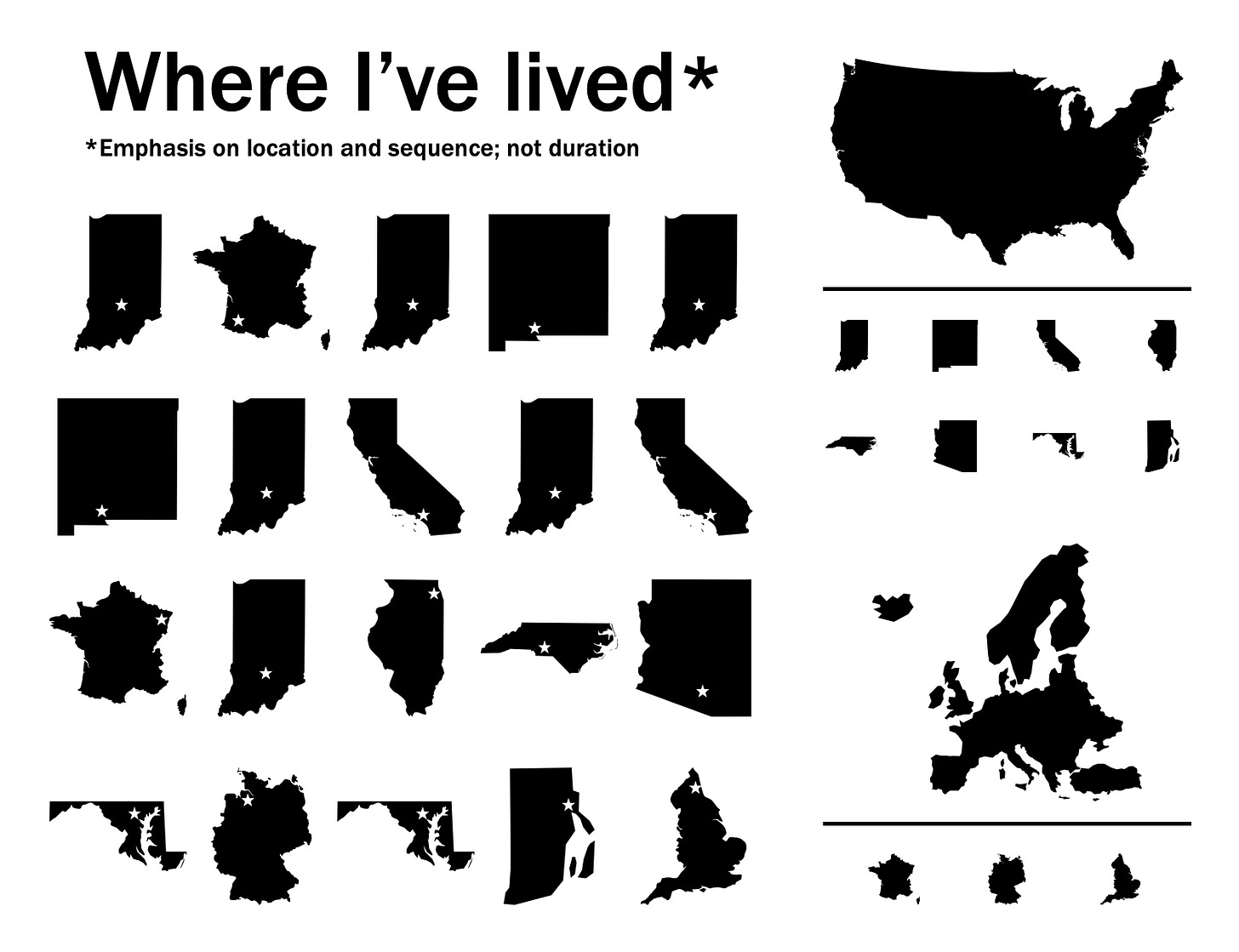

“Where are you from?” is a question that is at once geographical and social. My parents divorced when I was a couple of years old (relatively normal) and then swapped us back and forth over the course of my childhood (less normal). I’m not talking about parents who live across town from each other. I’m talking about parents living across country from each other, like Indiana and New Mexico, or Indiana and California. Just as examples. The longest I spent at any one school was three years, and even then the summers were spent elsewhere. I’m flummoxed when asked where I went to high school: two years in urban Southern California and two in rural southern Indiana is quite a combination.

An almost inevitable result is that there is no one place I feel comfortable saying I am from.1 I have no childhood bedroom waiting for my occasional visits, nor a box of high-school-era effects waiting for me to someday come to claim them. There is no place where I feel an immediate sense of belonging, or where people know my family.

My parents moved around after I was born, but even before that they had themselves moved away from their parents, who in their turn also lived away from their own families. I’m doing the reckoning, and I’d have to go back at least three generations to get to a place that might count as where my people are from. Whatever that means.

“Where are you from?” is a little like other seemingly benign questions such as “what do your parents do?” or “how many siblings do you have?” No one is expecting a complicated life story in response. They’re simply looking for you to say, “Amarillo” or “accountant” or “four”. I’m guessing a lot of us are uncomfortable with these questions and have manufactured mostly-true answers that are minimally satisfying to both asker and askee.

Hi, I’m From Pedant-Ville

Ok, ok. There’s probably more to my aversion to this question than the personal.

What about when people say they’re from Chicago? Or London? I can’t help wondering what that means. I may not say, “metro area or city?,” but you know I’m thinking it.

I definitely struggle with the spatial-scale aspect of the question. I can say I’m from Indiana, but Indiana is many things. It contains multitudes…and I wouldn’t want anyone to assume I’m from Indianapolis.

Aside from spatial specificity, I wonder, too, about the temporal. Is there a minimum duration or stage of one’s life that qualifies as being “from” somewhere? I was born in Indiana. Does that make me from there? I also graduated from high school and college in Indiana, but between those life course events I lived a variety of places that were not Indiana…or even Indiana-adjacent. What does it take to make a place an anchor?

In my case, needing to claim somewhere as home, I usually say I am from Brown County, Indiana. A friend of mine thinks this is really funny. He says I’m the only person he’s ever met who, when asked, says they are from a county and not a city or town.

Hear me out though. First of all, I’d argue counties are meaningful places in much of the Midwest. For example, the high school I graduated from is the county high school (for scale, there were approximately 160 teenagers in my graduating class, from across the entire county). In Indiana, at least, being from Brown County is recognizable and meaningful, so maybe that’s also why I do it. Google knows all about Brown County, Indiana.

Aside from that, the house I lived in for most of my time, age 5 to 12, is in a place called Needmore in Brown County. Needmore2 isn’t a town. It’s more of a geographic concept, really. No stores, churches, or streets or anything like that. No neighborhoods. Kids who lived in Nashville (population 705 in 1980), the one real town in Brown County, were Town Kids. Nothing like us Country Kids. Nashville kids had a Dairy Queen, an IGA, two stoplights, and their own elementary school. They had sidewalks.

My family had no indoor plumbing, an outhouse, and a wood stove. Our house didn’t even have an address when I was a kid. Instead, we were a mailbox number on “Rural Route 3.” In the summer, we’d walk barefoot, attempting to pop the tar bubbles that would emerge on the paved roads on the sunniest days. We caught crawdads in the creek for fun. In the winter, we’d cover the house windows with plastic and compete to stake a claim in the narrow space between the wood stove and the wall, where one had the best chance at warmth.

I tell myself these are not the experiences of a Town Kid from Nashville (although in hindsight there was probably plenty of poverty there, too), so it feels dishonest to say I come from there.

And for perhaps obvious reasons, explaining the details of where I’m from to strangers doesn’t sit right, either. So I say I’m from Brown County, and I am technically correct. Pedants rule.

It Matters Where You’re At

Context matters, too. Living outside the US, whether France, Germany, or now, England, my goal is to avoid being asked where I’m from. Usually it’s my accent that gives it away. My haphazard German announces I am not from Germany without my having to say so.

Sometimes, too, it’s nice to be able to say “I’m not from here.” I’m thinking back to my college years and the exotic nature of students from New Jersey. Foreignness can be an asset, a form of social currency.

And as I noted at the beginning, I love to ask people where they’re from: observing how far people have landed from where they say they started. Piecing together the peregrinations that link the here and now to the places that came before.

“Where Are You From?” Is a Social Construct

I am uncomfortable with questions like “where are you from?” because they make me feel exposed and, sometimes, forced to disclose more background than I like.

My real issue, though, may be that I am simply too good a geographer.

I know, right?

I realize the value of the question, but also its limitations. Being “from” a place is subjective, and yet I want it to reveal objective truths. But just as measures of migration or mobility depend on the definitions we assign them, so too do questions about origins and place. So I’ll continue to fine-tune my own answer, trying to accept that it may change over time, and that’s ok.

And vice versa: I can make a home almost anywhere.