Teething Problems

Last summer, on family vacation, one of my younger kids made a passing reference to The Time Mom Lost Her Front Teeth and my eldest responded, incredulous, that she’d never heard this story before. This was nuts, because this story is a Big Fucking Deal in the life of Rachel. It is a crucially important part of my own character’s back-story.

At the age of 12, walking down a gravel back road on my way to a babysitting job, my dog gave pursuit to a passing pick-up truck, ran directly into me, and knocked me down, face first. I lost one tooth, broke another, and bit through my bottom lip. Because we were poor and rural, my mother didn’t take me to an emergency room, but rather to the local doctor, who came into his office after hours and patched me up as best he could, which was honestly not very well—18 haphazard stitches, resulting in scar tissue I still tug at when anxious. A few weeks later, a local dentist filled the empty gap in my mouth but the broken tooth was obvious for several years. I simply wouldn’t smile with my mouth open.

In other words, this was a pivotal event, not only to middle-school me, but also adult me,1 so that I was also, in turn, gobsmacked that any of my children remained ignorant of this momentous occasion. My daughter was full of inquiries. How big was the dog, she asked. Who was driving the truck? She also had questions about dogs chasing cars, which I guess illustrates a key difference between rural kids in the ‘80s and city kids in the ‘00s.2 All the dogs chased cars where I came from. It was a thing.

If we’re talking origin stories, I am not saying mine is missing teeth, just that this fact was always there (in a way my front teeth are not), even if I rarely talk about it and it gets missed out in some versions of the origin story.

Geographical Origin Stories

I became a geographer by accident. This is a common enough confession. Usually, though, it’s because someone took a job on a research project and realised their true calling. Or took a college class with a dynamic geographer (we’re a pretty awesome bunch, after all) and experienced a sudden conversion. Me, I took a class, but didn’t understand the material at all. I did, however, take quite a shine to the geographers. They were smart and funny and very, very social. I wanted to be like them. (I’ve now had decades to confirm my initial impression and it hasn’t changed: of all the academics, across all the disciplines, geographers are the best.)

In a way, I became a geographer for the parties.

I jest. Sort of. That’s just one “how I became a geographer” construction I can build from the fundamental facts. Origin stories are slippery that way: yes, they’re anchors in time and space that provide a grounding for subsequent trajectories, but they’re anchors placed in shifting and subjective sands that are forever changing shape and evolving. Depending on the audience, where I am in life, and other contextual factors, a variety of narratives can emerge from the same fundamental facts.

I have tended to assume this is true of everyone, but lately am not so sure.

Over the past few years, I’ve worked with a couple of colleagues (shoutout to Dani Arribas-Bel and Levi Wolf) on a project called Spatial Analytics + Data: The Interviews, where we collectively engage in conversations with members of our field. Origin stories are always a central part of these interviews: how did people get where they are now? What do they view as the essential facts that anchor their narratives?

While many of our interviewees have settled on an origin story and stick to it across time and setting, many others we’ve spoken to have not: when asked how they got here, they have facts, but less binding narrative. Both types of interviewees are intriguing. We humans tend to like the logic and order of a fully formed origin story, right? So when it’s not there, we are bothered. But we also like to hear the same story told from different vantage points, or with new insights or perspectives that are added over time.

When we are interviewing and asking about origins, I often feel the task is a bit like shaking a snow globe and seeing if a different pattern of drifts will emerge. The snowflakes themselves are unchanging, as is the underlying topography on which they fall, but if we shake the globe just so, maybe a different pattern of facts—or origin story—will emerge.

I know that, depending how I shake my own snow globe, different key plotlines emerge.

The $1000 Baby

My favourite of my origin stories is the original, seminal one: how my parents ended up married and how I came to be.3 The details are shrouded in the mists of time (i.e., the 1960s and ‘70s) and come to me via my grandfather. I could ask my mother for verification, but why ruin a good tale with facts?4

This is the story of how my mother and father came to be married, when they were both still quite young. They’d been dating for a while in high school and then both went off to separate colleges, reconnecting when home. On one of these occasions, according to my grandfather, my father—his son—got caught one too many times sneaking over to my mother’s bedroom and her father (my other grandfather, who never once told me any version of this story at all), impatient and angry, issued an ultimatum to my dad, “Either stay away from my daughter or marry her”.

In a fit of rebellion (true love?), my father replied, “All right, then, I’ll marry her”. As my grandfather tells it, no one expected this outcome, but once set in motion, everyone was resigned to seeing it through.

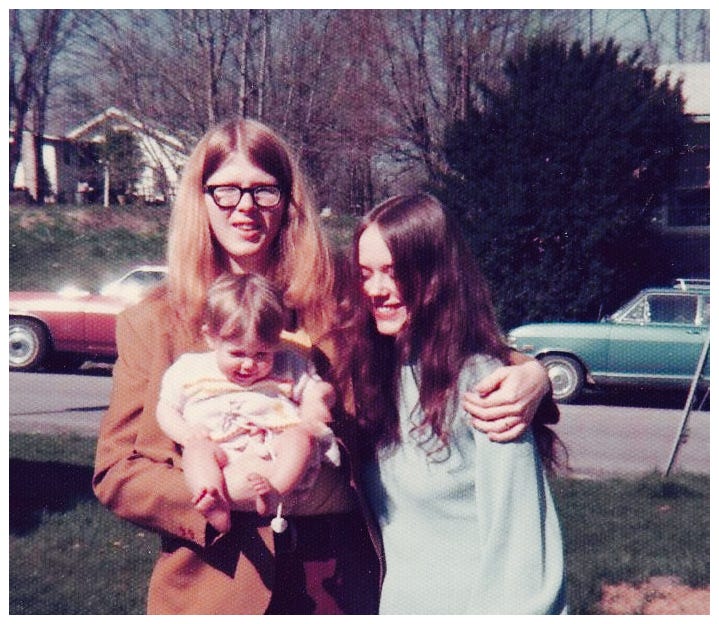

There are layers and layers to this story, not least of which is my grandfather’s evident pride in my father—the sneaking into the bedroom part as much as the sticking to his guns part. My grandfather is gleeful when telling this story. It also contrasts the two families, my mother’s, conservative Catholic, and my father’s, not. It also happens to be the only story I have about their wedding. They were both very young, neither family was particularly happy about the situation at the time, and I have never seen photos or heard stories about the wedding itself.5

Like many origin stories, it is also one told by others.

My parents have both directly shared the details concerning How I Came to Be, however. Newlywed, it was decided that they would both transfer to Indiana University and continue their undergraduate degrees there. In some tellings of this story, it sounds a bit like a punishment: exile to Bloomington. In others, it’s just a logical compromise on location and finances.

In any event, soon after, my mother dropped out, got a job at the local A & W as a carhop, and decided she’d like to have a baby.6 My father’s response was that, if my mom could save $1000, they could have a baby.7 And so she did, and so I came to be.

I love my origin story.

To be clear, over time, I’ve felt more than a bit of regret that there wasn’t sufficient support to keep my mother in college—you don’t have to be a rocket social scientist to know the lifelong impacts that leaving university will have had on my mother’s choices, economic security, or retirement situation. If only things had been different.

Apart from that, I love that my mom was 19 when she had me, yes, but she was married! I was planned! I was not an accident.

Takeaway

I feel like there should be a moral to this essay. If there is, I think it’s: figure out a version of your origin story, even if it evolves with time and experience.

And, academics, you need a Google scholar page, a website…and an origin story. People want to know where you started, where you’ve been, and where you see yourself heading.

Funny Tidbit (I think this is the best part)

If you’ve read the footnotes, you’ll have seen that my mother sent me lots of contextual information about my non-geographical origin story (thanks, Mom!). This was my favourite bit, about preparing for my birth:

“Your ‘due date’ was 2 weeks past when I thought, the hell with it, I'm never going to have this baby, I want pot roast! So we had a huge dinner, labor started, and I got pretty sick. We called a cab in the middle of the night and the cab driver was very nervous and hit all the bumps, it seemed!

I had done a Lamaze class. My mother said, ‘I don't want to be rude at all, but I thought you liked drugs! Why on earth would you not take drugs on that one day?’”

All the painful dental work over the years; all the anxious dreams about crowns not holding fast; and, even now, decades later, all the self-consciousness about smiling with my teeth showing.

And also some big differences between city dogs and country dogs.

When I told this story in the pub a few weeks ago, my friend, Steve, said, “Oh, so you were the $1000 Baby!” I owe him a pint of Landlord for the suggestion.

Kidding. Yesterday I sent my mom an email, subject line, “Fact Checking”. See other footnotes for additional details.

According to my mom, “[my uncle] was taking a photography class, so he offered to take pictures. He didn't pay attention to what he was doing, and every single picture was marred by somebody moving. I don't think we posed for any of them. There was no honeymoon, of course.”

This is sad: the dropping out, my mom explains, was that her father refused to pay that semester’s tuition. I know, I know: maybe you’re thinking this is a natural outcome of a decision to get married and commence adulthood. My mom was 18.

It’s good to write your mom and ask her stuff. She tells me that “Before the wedding, [your dad’s dad] said he would only give his consent if I got on the pill. He loved to repeat the story I told him of the social worker at Planned Parenthood asking why I was there. ‘My father-in-law insisted,’ I sighed, and she said, ‘I never heard that one before!’”

I can point to three specific events that led me to geography:

1. Elementary school. My parents bought a set of Funk & Wagnells encyclopedias. They could buy a different volume every week or two at a local grocery store. I remember reading the entries for various US states and seeing small maps with icons indicating the locations of cultural highlights, natural resource locations, and the largest populated places. I remember thinking that the maps were very cool and I wanted to know why the icons were where they were.

2. Middle school (specifically 6th grade). South Dakota required middle schoolers to take one semester of geography. My teacher, Mrs. Hillestad, was unbelievably good at making the topic come alive - she won the South Dakota Teacher of the Year award the year I had her ! It was my favorite class in all of middle school and showed me how interesting geography was.

3. High school. During the summer after my junior year (1994), I went to a two week summer program at Oak Ridge National Lab in Tennessee. I indicated my interest in geography on the form and was assigned to a project to map with curb cuts and loading docks on the main campus. We printed out large maps of the building footprints and streets. Then, we drove around the campus marking their locations on the paper maps. We went back to the computer lab and used MapInfo to generate GIS files for curb cuts and loading docks. This was my first exposure to GIS and convinced me that my interested in geography was worth pursuing in college.

Maybe I still would have ended up a geography major, but those events certainly helped!

I was in study hall, sophomore year of high school, when a new teacher arrived mid-year and gave out assigned seats. I kept talking to people next to me, so he moved me over by some cheerleaders. I had longer hair and I have big fingernails so they were doing my hair and painting my nails so he moved me again over to some jocks who thought I was hilarious so he moved me over to a bunch of Mexican guys I grew up playing soccer with.... So he parked me in a corner, solo.

I was staring at the ceiling when he came up and asked me "Don't you have homework?" "Of course." "Well... shouldn't you be doing it?" "The ceiling is more interesting."

Figuring he would be teaching me a lesson, he handed me a college-level geography textbook and told me I needed to read Chapter 7 and explain it to him or he would send me to in-school suspension for my various transgressions over the span of January. The next day he called me over, arms crossed and asked for my summary. He looked pretty stunned. I said "I'm not stupid. I just don't do things I don't want to do."

He got me signed up for one of his geography classes in the fall; he signed me up for Model UN and told me about it later after he told my mom about it (which was like committing me to a blood oath), he never kicked me out of class for the things I did (mostly antagonizing the shitty kids surrounding me).

If Mr. Stewart hadn't taken a shine to a slacker, I'd probably be a welder.