I’ve had a bee in my bonnet for some time now, where data is concerned. Either the bee has been getting louder or my hearing has been improving; either way, I’m finding it increasingly difficult to ignore the buzzing.

In my little corner of the world1 all we seem to talk about these days is data. Not volume, variety, or velocity. No, we’ve graduated to exhaustive—and exhausting—conversations about representation, privacy, ethics, and access. To be clear, these are all really valuable discussions. No matter how important our research arena, whether health, climate, or inequality (to name just a few), it is right that we be interrogating ourselves and others about the suitability and appropriateness of the data we are employing to answer our research questions.

You Say You Want a Revolution

Why are we having these conversations? Blame the data.2

Accidental, smart, found, exhaust, trace, digital footprint, organic—whatever you want to call it.

These are data types not intentionally collected for research purposes, but their quantity, scope, and content render them hyper-alluring for a range of research applications. Here I’m referring to social media, mobility, app, or sensor data, for example. Aside from the potential for brand new insights—answering questions about real-time behaviours, daily mobility, or health or nutrition preferences, for example—the magnetic attraction of a novel source of data that hasn’t previously been explored is almost too much for data-oriented researchers to resist. There’s something so exciting about new data. I am deeply empathetic.

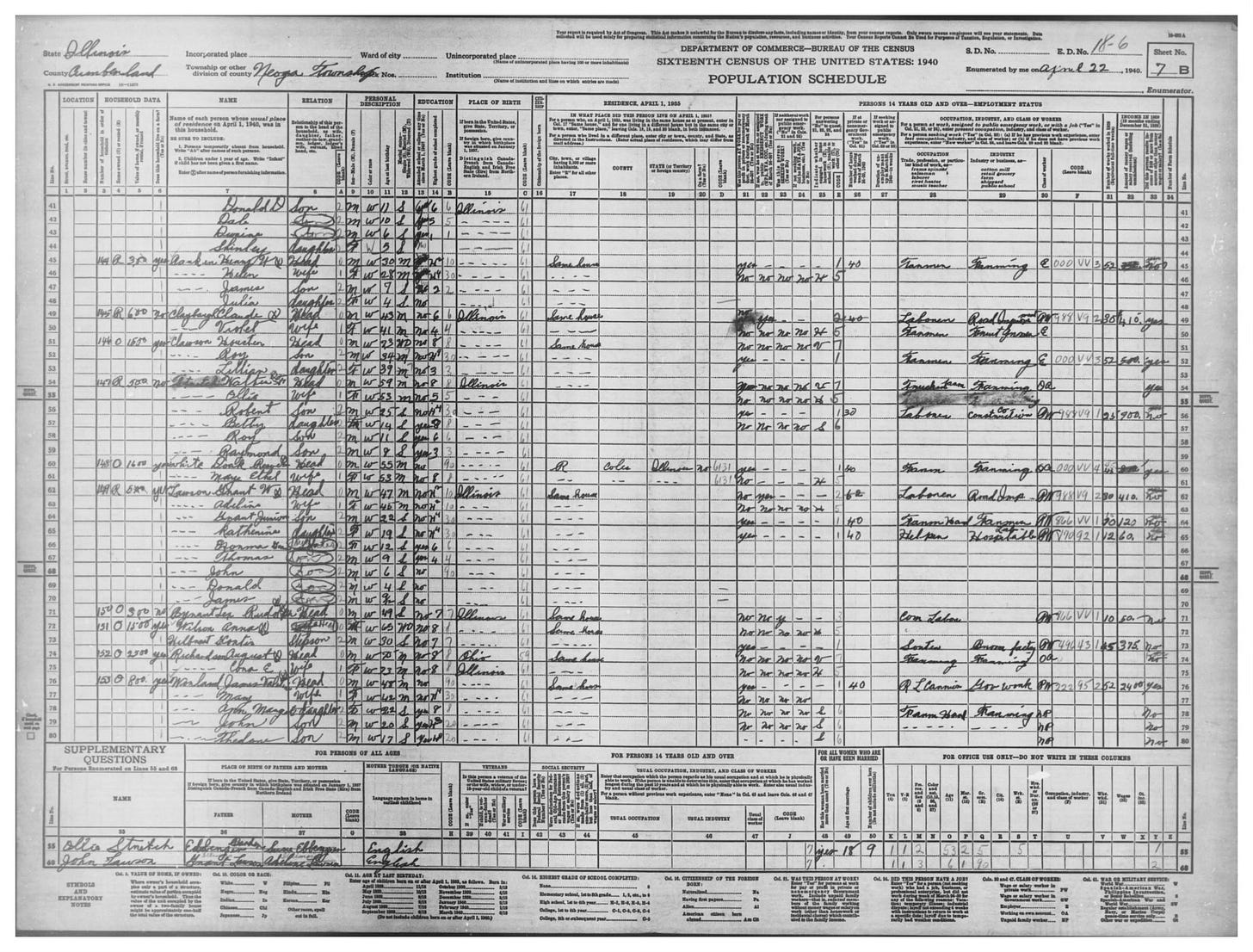

That’s a pull factor. We’ve also got push factors, though, as any social science researcher accustomed to working with survey and census data will tell you. Censuses are expensive and respondents are increasingly hesitant to take part. Surveys suffer from low response rates and attrition. All our careful statistical groundwork around representativeness and coverage is at risk (or already failing). Governments, who generally foot the bill, whether directly or indirectly, via research funding, are increasingly loath to spend money on an unpopular, possibly ineffective, and deeply un-sexy3 endeavour. It’s poor value for money, as they say. This makes alternative data even more attractive to researchers: if our traditional data sources are about to disappear or become unreliable, why not make the jump to newer forms of data before we are pushed?

There’s a cynical perspective too, which is that it can be easier to publish a boring finding with novel data than a novel finding with boring data. But that’s a conversation for another day.

You Tell Me That It’s Evolution

Anyway. Back to that buzzing data bee. I’m sure I can’t be the only one, but for some time now I’ve felt a sense of unease at the ways in which my community4 and the quantitative social sciences more broadly are handling the tension between novel and traditional forms of data and, especially, how we are rationalizing the choices we are making. Because, let me be clear, we are making choices! Every time we justify trade-offs between ethics and compelling research question, lament the demise of censuses as a natural death, excuse the unreliability of new forms of data, or take as a given the fact that corporations are the default owners of information about us, we as researchers are contributing to a shift in data infrastructure that is at least partially voluntary.

You Can Count Me Out

The trouble with my bonnet buzzing over the past year or two is that it has been difficult to distinguish signal from noise. What is bothering me? Perhaps I’m just a data dinosaur.5 Perhaps it’s that I’m naïve or inexperienced.6 Maybe I just like to argue.7 I’m still working it out, but I think I’ve now settled on a few things.

Abnegation of Agency

We can argue about data- versus theory-led research all we want, but the plain truth is that the typical quantitative research flow is something like:

I have a research question; what data can I use to answer it?

Here’s some cool data; what can I do with it?

But there used to be a third option, I am convinced:

What sort of data do I need in order to be able to address this question?

It is this third type of research flow that gave us the longitudinal and cohort studies we have, as well as many of the interesting surveys and census-related data collection mechanisms we are used to. These traditional, old-fashioned data sources are the result of a choice to invest in building the foundational tools needed to respond to big societal challenges.

The thing is, I don’t think we’re investing less funding in data now. This isn’t about appetite to invest in data infrastructure. Rather, we seem to have collectively thrown up our hands and agreed that, as researchers, we have no alternative and must make do with the data-in-the-wild that we are lucky enough to gain access to.

This still comes with enormous actual costs! We pay for data, we dedicate enormous time and money resource to ensuring data access, to assess whether data is fit for purpose, and to fill identified weaknesses.

My point is that we tend to treat our current data landscape as a thing that is foisted upon us, but we have agency in terms of where we invest our data energies, resources, and expertise.

Ethics

I’ll keep this one short. Just because we can use digital trace data from, e.g., people’s mobile phones or apps or other devices doesn’t mean we should. And it’s remarkable—if you ask a group of spatial scientists whether they care about being tracked, many of them (like me) will say they take whatever meagre measures they can to limit how much information is collected about them. This makes me hesitant about using such data in my own research. Is it ok to use the data produced by other hapless users who may not be as well informed as we are?

In Thrall to Big (Corporate) Data

Another small point: how did we get ourselves into a situation in which profit-seeking firms are the keepers of information that researchers need in order to help make the world a better place and also build careers?

This isn’t about data access agreements, legislation, licensing, or other mechanisms to encourage data owners to share. It’s not about investing in data infrastructure to leverage all this data. It’s about having frank conversations about whether this is where we want to dedicate our money and energy and whether we’re ok with the inevitable conflicts of interest when we and the data owners are optimising on different criteria.

Validation

This is one that makes me laugh, albeit sort of wildly. Most of the novel forms of data we rely on do not provide us information about who is doing the moving, using, choosing. For demographic characteristics we rely on what? That’s right: high-quality traditional data sources. If we want to depend on new data, we really have to care for and nourish our traditional forms of data.

Side note: I am pretty bullish on linked administrative data, but somehow it’s rarely part of the data conversation. We should be talking about it more.

Data and the State

Something that is lost in conversations about publicly-funded data collection like surveys and censuses is the collective, civic function that they serve.

It confounds me when I am in a conversation about how folks these days just won’t respond to surveys because they don’t trust the government or don’t answer their phone. All the brain power we invest in smart data analysis and we can’t figure out how to develop novel ways to collect good data or communicate to people about the value of their contributions? Weird.

More than that—and here I am thinking primarily about censuses—I very very VERY strongly believe that there are few remaining ways we come together as a collective society, and in many countries the census is one of them. It is a thing that we build together and that’s irreplaceable from a civic standpoint. Smart data owned by private entities cannot fulfil that role for us.

Yay, census!

A Flash in the Pan?

The slow-motion implosion of Twitter/X has highlighted another aspect of these emerging forms of data: they may be far more transitory and ephemeral than we initially believed. I don’t just mean that data cease being available, although that’s absolutely a thing. The potential problem is much bigger than that. What if what we thought was a new data world order (social media, widespread user tracking, etc.) was simply a short-lived era before data closed back up or dried out? Remember when we were all excited about what we might be able to learn from Facebook? Twitter? Ha. I’m old enough to remember Foursquare. And this is before considering the stifling effects of stiff government intervention and regulation, which we are likely to start to see more of.

A Real Solution

New forms of data are cutting edge and innovative and, yes, super cool and intriguing. Trust me, I get it.

But you know what would be really, really innovative? Figuring out how to combine state-of-the-art technology and data-collection mechanisms (smart devices, sensors) to build new or augmented surveys, datasets, and (maybe) even censuses. This is hard work but that also makes it a cool challenge. Also, it can help to address issues around explicit consent, representativeness, and suitability.

For example, imagine collecting mobility data from individuals or vehicles in this fashion. We know we possess the technical tracking capacity because we already do it. Yes, yes: there are potentially small sample sizes and issues around representativeness. But we already deal with the latter and this is also a timely opportunity to ask what sort of sample size is required in order to answer the question we have. Is BIG worth all the hassle we are currently dealing with? This is also a chance to obtain fully informed consent, develop longitudinal data over longer periods of time that are combined with socio-economic variables, and energise the general public about collective data needs and goals. I’m very here for it.

We’d All Love to See the Plan

A girl can dream, right?

In truth, I think our data future is probably hybrid: something old combined with something new, where data is concerned. If you know me, you know I love to talk data, new and old.

But to make the best use of new data, we really need to devote attention and resource to old data. We must also find our voices as researchers and believe that we have options and choices in the data we use in our research; we don’t only have to content ourselves with what is allowed to us.

We can also think big and leverage our collective expertise to design the data products that are needed in order to respond to the big environmental, social, and economic challenges that face us.

What do you think? I probably missed some big points. On the plus side, my head is a lot quieter now.

Academic and at the intersection of geography and data science.

But actually: these are conversations it’s instructive and enlightening to have about all data.

I really think the sexiness has a lot to do with it: old is not shiny and exciting and politicians and civil servants often feel they need to deliver something different from previous administrations and eras.

Depending on the day: quantitative human geography, geographic data science, urban analytics

I mean, I’ve occasionally contemplated an “I ❤️ Census” tattoo, so…

Probably not.

Definitely.

Very entertaining, humorous, and informative substack, as per!