The pandemic has put the kibosh on study abroad programs for many universities, at least temporarily. Thinking about all the students missing out on this opportunity makes me sad. Pandemic and lockdown also heighten my awareness of away-ness and how much I value it. So for this second edition of “practicing geographer” I’ve written a love letter of sorts to international exchange and foreign language learning. It’s also a love letter to youth, doing stupid stuff, and the friends made along the way.

In February, 1993, I had a grand idea. Midway through my junior year abroad in Strasbourg, France, and feeling pretty acclimated into my new environment, I thought it would be fantastic to drive to Avignon and hunt up my high school friend, Becky, who had just arrived in that city to start her semester abroad.

Did I know where Becky lived? No.

Did I have a way to contact her to say I was coming? No.

Did I have a car? Again, no.

However, these seemed minor impediments to success; I was certain that Avignon was sufficiently small and Becky sufficiently American that an accidental encounter on the streets of Avignon was inevitable. Turns out it was evitable.

Avignon is a solid six-hour drive from Strasbourg. We drove down, my accommodating, car-owning Italian boyfriend and I, walked around the city with eyes peeled for the elusive Becky, and then drove home to Strasbourg. Pretty sure we did it all in one day and we didn’t even break up afterwards.

(I was 19. I feel this is a non-negligible contextual detail.)

Allons-y | Let’s go

I am not someone who, given a chance at parties, eventually turns to droning on about my junior year abroad in France…almost 30 years ago (I’m much more fun than that, I promise). The fruitless Avignon trip isn’t even a defining story of that year. I am, however, increasingly a person who feels the need to shout about the intrinsic value of foreign language study and time abroad—and not a few weeks or months abroad, but a good solid year: enough time to think you’ve mastered the language and culture and then realize that, holy shit, you don’t actually get the half of it.

A year offers ample opportunity for adventure, as well.

The times we live in are paradoxically unfriendly to study abroad. I say paradoxically because we live in an era of globalization: experience and facility with other cultures should be an easy sell to students, parents, and employers. Unfortunately, we also live in times of risk aversion, especially where parents and young people are concerned. Moreover, we treat time in university (and high school) as a time to be industrious and constantly moving forward. Languages and study abroad can seem frivolous. I wish we’d stop treating education this way, but that’s for another time.

Overseas study tends to be framed in terms of utility: life-changing experiences that will help students stand out to employers and give them a leg up on the career ladder. I am not sure how language study is justified but it seems much more marginal than it used to be. Maybe take a few years in high school to get you into college and that suffices? Definitely, in keeping with a lot of education at the secondary and university levels, language and overseas study has to be useful. No learning a language or studying abroad just for fun.

Fun is good. Fun is the leavening in an otherwise heavy pursuit.

Hoosiers Represent. Here I owe a quick shout-out to my undergraduate institution. Indiana University made foreign language study and international exchange easy. Language requirements for most degrees meant there was lots of choice and everyone seemed to be taking Spanish or French or Japanese. This is important when you’re young. Year abroad programs were accessible and participation almost frictionless. All credits in Strasbourg transferred back and counted towards my degree. I paid my usual in-state tuition and my financial aid applied as usual.

Allant | Going

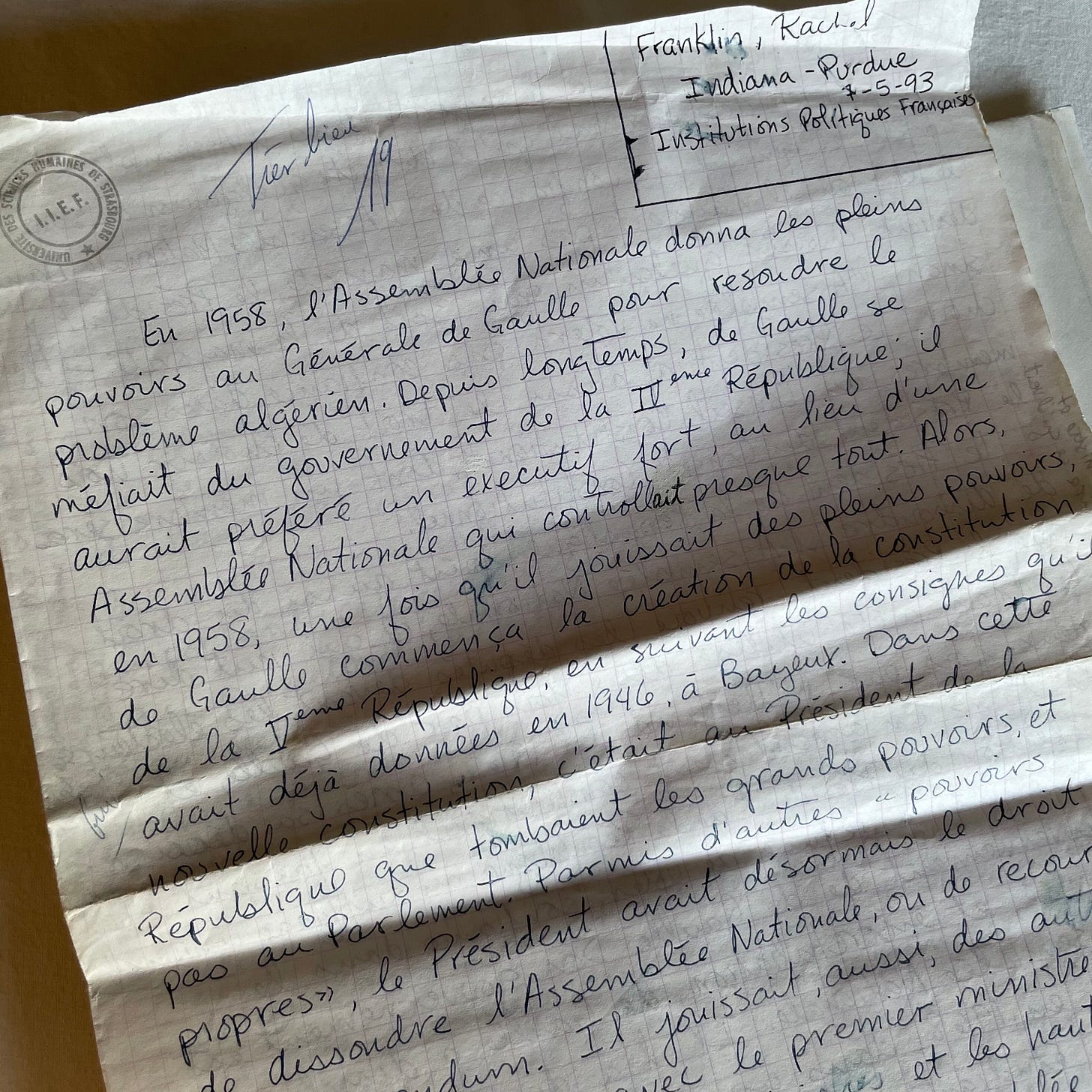

I learned so much French language and culture the year I lived in Strasbourg, but little of it was in classrooms. I read books, went to movies, and clumsily flirted with boys in bars. I haphazardly attended class, astounded that lecturers would walk into a room, orate, and then leave. No discussion, no questions. I was appalled to discover that, although grades were given out of 20, I should be grateful for even a 12. A 16 would be fantastic. I won’t speak of my experience with oral examinations, except to say that they were humbling. After fumbling through one particularly harrowing end-of-year oral exam, I was asked by the professor if I’d actually learned anything in his class. Of course, he asked in French and I understood—so I suppose the answer is yes?

Young and not much of a partier, my American friends taught me to drink Kronenbourg 1664 at home and then head out late to the bars. I learned the phrase “faire la nuit blanche” by doing it a couple of times. I also learned that this was not for me.

I didn’t make so many French friends in Strasbourg, which was initially a disappointment. Now, looking back, I think about how much we learn from a culture when something doesn’t happen. My guess is it wouldn’t be substantially easier to be an exchange student in the US, either. Some cultures are simply friendlier than others. In contrast, I made lots of Spanish friends. Those students, on exchange to Strasbourg for the year through the Erasmus program, were open and embracing of new additions to their friend group.

Know who else is friendly? Italians.

I went home with the Italian boyfriend for Christmas. I made tortellini with his mother and then listened, throughout the meal, as each person held up their spoon and said, “Ah, here’s one made by Rachel.” Or Rachele, actually.

The parents gave us a shared bedroom with a large crucifix over the bed and across the hall from an elderly bed-bound grandmother who would occasionally shout numbers…novantatré! settantotto! I have no idea why she did this, but it was excellent for my counting skills.

I got to drive a Fiat 500 and learned to make pasta carbonara. The latter turns out to be an important life skill, the former not so much.

Away for a year, I took lots of trains and visited lots of cities, and also ate lots of croissants, drank many coffees in cafés with friends, and learned a lot about solitude and self-sufficiency. Went to Paris so many times that it stopped being a big deal. Went back to Avignon and found Becky (!) and took her on a whirlwind Easter road trip. That actually is one of the top stories from that year.

The missed encounter with Becky notwithstanding, twice that year the serendipity of unexpected encounters did resolve nicely. One was a college friend from the US, backpacking through Europe and hoping to find me. I happened across him one evening sitting on a bench outside a university building, taking a rest with his enormous American backpack.

The second time, I was standing in the Prague train station with my younger sister, tired and anxious about where to travel next on our Eurail passes, and a woman behind us in line interrupted our conversation to ask my sister’s name. Trying to be polite but also cautious, my sister answered, only to have the woman respond, “Hi Abby, I’m your Aunt Susan.”

<<Et maintenant, on fait la bise>>

This pandemic year, I’ve marked nearly every week with apéro-zoom with my two closest friends from that year, both American, both still using their French on a daily basis. We’ve stayed in touch since college, usually with a visit or two every year, and our kids have all grown up together. And Becky, my friend from high school, is still very much a part of my life. I can’t say France is the reason for the duration of these relationships, but I can’t say it’s not, either.

Reading what I’ve written above, I note my tendency to talk about what I “learned” that year—in spite of my own protestations, the impulse to justify study abroad as edifying is strong, even though some of the main benefits have been the relationships. So, thinking on it, I made a very short list of some stuff I actually did learn that year:

You’re going to need a bigger suitcase. Don’t let your parents send you to France for an entire year with only one suitcase. Pack extra shoes and a warm coat in case you end up in a city that turns out to be referred to as the “Siberia of x.”

The difference between vas-y and va-t-en. This one’s important. Subtle differences that mean all the difference between telling someone to go ahead or go away.

Erasmus is awesome. Exchange programs are valuable institutions that should be preserved and treasured.

Italian. Learn it, it’s great.

But seriously. Let’s normalize being a little bad at something and then getting better. Let’s teach our children the same. Learn a language. Study abroad. God, I miss being anywhere other than home.

I’ll end with an anecdote from my own parenting experience. Shortly before her French AP exam in high school, my daughter went to stay with one of the apéro-zoom friends for a couple of weeks just outside Paris, in Saint-Cloud. She’d take the train into Paris and wander around all day and then come home in the evening. With very limited phone data and even more limited independent travel experience, adventures were had. Trains were taken in the wrong direction (she still reports the SNCF jingle as triggering) and more than once she found herself completely lost.

One day, all turned around in central Paris and trying to orient herself on a map, a man stopped and asked to help. He explained where to go and then said, “et maintenant on fait la bise”—and now we French-style kiss. Hearing this story later, the parent in me narrowed right into all the not-good aspects of this encounter with a clearly lost 16 year old girl with imperfect language skills. Upon reflection, though, it’s a great story, one that she (and I!) will tell for years to come. Most importantly, my child handled the experience successfully, without need for me to intervene or protect. An adventure all of her own.